Exam Details

Exam Code

:SBACExam Name

:Smarter Balanced Assessment ConsortiumCertification

:Test Prep CertificationsVendor

:Test PrepTotal Questions

:224 Q&AsLast Updated

:Jun 29, 2025

Test Prep Test Prep Certifications SBAC Questions & Answers

-

Question 211:

FILL BLANK

A student earns $7.50 per hour at her part-time job. She wants to earn at least $200.

Part A: Enter an inequality that represents all of the possible numbers of hours (h) the student could work to meet her goal.

Part B: Enter the least whole number of hours the student needs to work in order to earn at least $200.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 212:

FILL BLANK

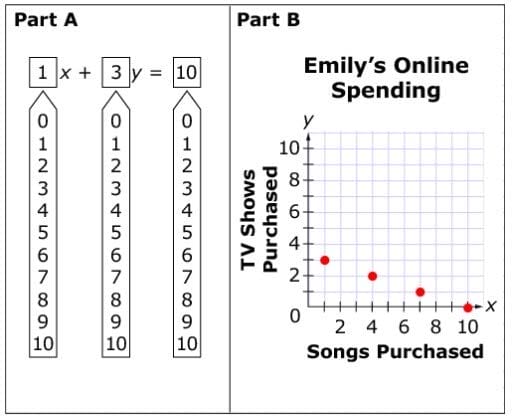

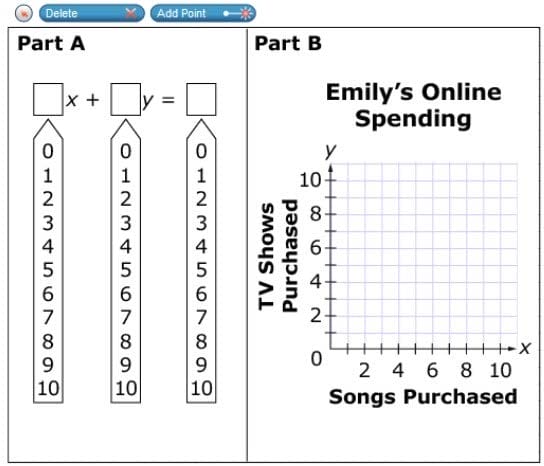

Emily has a gift certificate for $10 to use at an online store. She can purchase songs for 1$ each or episodes of TV shows for 3$ each. She wants to spend exactly $10.

Part A

Create an equation to show the relationship between the number of songs, x, Emily can purchase and the number of episodes of TV shows, y, she can purchase.

Part B

Use the Add Point tool to plot all possible combinations of songs and TV shows Emily can purchase.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 213:

FILL BLANK

Place a point on the coordinate grid to show each x-intercept of the function. Place a point on the coordinate grid to show the minimum value of the function.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 214:

FILL BLANK

Mike earns $6.50 per hour plus 4% of his sales.

Enter an equation for Mike's total earnings, E, when he works x hours and has a total of y sales, in dollars.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 215:

FILL BLANK

The basketball team sold t-shirts and hats as a fund-raiser. They sold a total of 23 items and made a profit of $246. They made a profit of $10 for every t-shirt they sold and $12 for every hat they sold.

Determine the number of t-shirts and the number of hats the basketball team sold.

Enter the number of t-shirts in the Part A.

Enter the number of hats in the Part B.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 216:

FILL BLANK

Read the text and answer the question.

Moving to the Back of Beyond

When my parents said the three of us were moving out to California, to a place just north of Los Angeles, my mind immediately went to thoughts of Disneyland and Hollywood, glitz and glamour. I imagined a Rodeo Drive shopping spree to

pick out a bikini for the endless days I would be spending on the beach. However, I’d forgotten about my parents’ penchant for the unconventional; they’re definitely “the road less traveled” kind of people. Mom had a gopher snake for a pet

when she was younger, and Dad was never happier than when he was climbing near-vertical cliffs that only mountain goats could love. These are not city folk.

They had chosen to buy a 900-square-foot cabin under a 250-year-old oak tree in the high chaparral1 forest out in the back of beyond – so far away from Los Angeles that you couldn't even see the glow of the lights at night. When I first saw

where we were going to live, I vacillated between feeling terrified and excited. This would be an adventure, for sure. But this was no camping trip where you could go home to civilization after a few days of roughing it; this was home, and

roughing it was the new normal.

On move-in day, we drove fifteen miles out from Antelope Valley – where the nearest grocery store was located – on a two-lane road past llamas, cattle, and horses. Up and up we went, until finally we turned down a dirt road and headed into

a canyon full of towering Coulter pines, blue-green sagebrush, and ancient canyon live oaks. I didn't know the names of these plants then, of course; I learned them later. That first day all I saw then was a million shades of green.

We parked under an oak tree that shaded our cabin and a front yard of rock, sand, and sagebrush twice as large as the cabin itself. On the stone staircase that led to the front door, black lizards interrupted their push-ups to twist their heads

and eye us as we passed. Scrub jays squawked and hummingbirds zoomed past the eaves, scolding us with their territorial calls.

No cars roared past. No radios blared from a neighbor's house. There were no neighbors – no human neighbors, anyway.

Our new home consisted of one bedroom, one bathroom, and one big room for everything else. A fireplace in the corner of the big room would be our sole source of heat in the winter. A swamp box (cooler) would blow a breeze over a big

damp pad to keep us cool all summer, or so my father said. But it was early autumn that day, and the temperature was perfect in the shade of the oak tree. Our oak tree, I thought; I was settling in.

Mom wiped a layer of grime off the kitchen counter and muttered about getting a bottle of bleach on our next trip into town. That was the beginning of an important lesson about living in the back of beyond: you don't just zip over to the local

convenience store anytime you need something out here. You have to make a careful list and check it twice so that you don't forget anything, because anywhere is a long way from here.

On my first walk around the property, I saw two horned toads, a red-tailed hawk, and some deer tracks. I wondered what else I might find deeper and higher in the canyon. Dad told me the real estate agent had mentioned that coyotes,

bobcats, mountain lions, rattlesnakes, and even bears roamed these hills. To my surprise, I found I couldn't wait to see them. All of them. I felt my feet taking root in the earth, claiming this place as home.

With no street lamps timed to turn on at sunset, when night came it was darker than anything I had ever experienced. Mom and I went out to look at the stars while Dad tried to unplug the ancient toilet. In the city, or even in the suburbs where

I had lived before, you could see only the brightest stars in the sky. But out here, it was like being in a planetarium, except there were no labels typed onto our sky. The sheer number and spread of stars was awe-inspiring.

That first night, we slept on air mattresses on the living room floor because the movers had not yet arrived. There were no curtains on the windows, so when the moon rose, it shone in as if moonbeams were an integral part of the cabin.

Eventually, I moved into the bedroom and Mom and Dad got a foldout bed for the living room. Over the next few months, I began to count the passage of time in full moons rather than by the pages of a calendar, and for the first time I really

noticed the days growing shorter in winter and longer in summer.

It's hard to believe, but we’ve been here for six years now. I’ve been going to school in the valley, but I feel most at home up here with my wild fellow canyon dwellers. Soon, I will have to leave home for college, and I’m a little afraid of the

culture shock I’m sure I will feel when I move back to civilization. Soon I’ll be walking on pavement and well-mowed grass again, rooming with strangers, and eating meals in a cafeteria crowded with more people than live within twenty miles of

this house. But I know I will come back. The back of beyond is home now.

1. chaparral: a dense thicket of shrubs and small trees

The reader can conclude that the narrator is open to living at “the back of beyond” and accepts her new life there. Click three sentences that best support this conclusion.

Our new home consisted of one bedroom, one bathroom, and one big room for everything else. A fireplace in the corner of the big room would be our sole source of heat in the winter. A swamp box (cooler) would blow a breeze over a big damp pad to keep us cool all summer, or so my father said. But it was early autumn that day, and the temperature was perfect in the shade of the oak tree. Our oak tree, I thought; I was setting in.

Mom wiped a layer of grime off the kitchen counter and muttered about getting a bottle of bleach on our next trip into town. That was the beginning of an important lesson about living in the back of beyond: you don't just zip over to the local convenience store anytime you need something out here. You have to make a careful list and check it twice so that you don't forget anything, because anywhere is a long way from here.

On my first walk around the property, I saw two horned toads, a red-tailed hawk, and some deer tracks. I wondered what else I might find deeper and higher in the canyon. Dad told me the real estate agent had mentioned that coyotes, bobcats, mountain lions, rattlesnakes, and even bears roamed these hills. To my surprise, I found I couldn't wait to see them. All of them. I felt my beet taking root in the earth, claiming this place as home.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 217:

FILL BLANK

Read the text and answer the question.

Moving to the Back of Beyond

When my parents said the three of us were moving out to California, to a place just north of Los Angeles, my mind immediately went to thoughts of Disneyland and Hollywood, glitz and glamour. I imagined a Rodeo Drive shopping spree to

pick out a bikini for the endless days I would be spending on the beach. However, I’d forgotten about my parents’ penchant for the unconventional; they’re definitely “the road less traveled” kind of people. Mom had a gopher snake for a pet

when she was younger, and Dad was never happier than when he was climbing near-vertical cliffs that only mountain goats could love. These are not city folk.

They had chosen to buy a 900-square-foot cabin under a 250-year-old oak tree in the high chaparral1 forest out in the back of beyond – so far away from Los Angeles that you couldn't even see the glow of the lights at night. When I first saw

where we were going to live, I vacillated between feeling terrified and excited. This would be an adventure, for sure. But this was no camping trip where you could go home to civilization after a few days of roughing it; this was home, and

roughing it was the new normal.

On move-in day, we drove fifteen miles out from Antelope Valley – where the nearest grocery store was located – on a two-lane road past llamas, cattle, and horses. Up and up we went, until finally we turned down a dirt road and headed into

a canyon full of towering Coulter pines, blue-green sagebrush, and ancient canyon live oaks. I didn't know the names of these plants then, of course; I learned them later. That first day all I saw then was a million shades of green.

We parked under an oak tree that shaded our cabin and a front yard of rock, sand, and sagebrush twice as large as the cabin itself. On the stone staircase that led to the front door, black lizards interrupted their push-ups to twist their heads

and eye us as we passed. Scrub jays squawked and hummingbirds zoomed past the eaves, scolding us with their territorial calls.

No cars roared past. No radios blared from a neighbor's house. There were no neighbors – no human neighbors, anyway.

Our new home consisted of one bedroom, one bathroom, and one big room for everything else. A fireplace in the corner of the big room would be our sole source of heat in the winter. A swamp box (cooler) would blow a breeze over a big

damp pad to keep us cool all summer, or so my father said. But it was early autumn that day, and the temperature was perfect in the shade of the oak tree. Our oak tree, I thought; I was settling in.

Mom wiped a layer of grime off the kitchen counter and muttered about getting a bottle of bleach on our next trip into town. That was the beginning of an important lesson about living in the back of beyond: you don't just zip over to the local

convenience store anytime you need something out here. You have to make a careful list and check it twice so that you don't forget anything, because anywhere is a long way from here.

On my first walk around the property, I saw two horned toads, a red-tailed hawk, and some deer tracks. I wondered what else I might find deeper and higher in the canyon. Dad told me the real estate agent had mentioned that coyotes,

bobcats, mountain lions, rattlesnakes, and even bears roamed these hills. To my surprise, I found I couldn't wait to see them. All of them. I felt my feet taking root in the earth, claiming this place as home.

With no street lamps timed to turn on at sunset, when night came it was darker than anything I had ever experienced. Mom and I went out to look at the stars while Dad tried to unplug the ancient toilet. In the city, or even in the suburbs where

I had lived before, you could see only the brightest stars in the sky. But out here, it was like being in a planetarium, except there were no labels typed onto our sky. The sheer number and spread of stars was awe-inspiring.

That first night, we slept on air mattresses on the living room floor because the movers had not yet arrived. There were no curtains on the windows, so when the moon rose, it shone in as if moonbeams were an integral part of the cabin.

Eventually, I moved into the bedroom and Mom and Dad got a foldout bed for the living room. Over the next few months, I began to count the passage of time in full moons rather than by the pages of a calendar, and for the first time I really

noticed the days growing shorter in winter and longer in summer.

It's hard to believe, but we’ve been here for six years now. I’ve been going to school in the valley, but I feel most at home up here with my wild fellow canyon dwellers. Soon, I will have to leave home for college, and I’m a little afraid of the

culture shock I’m sure I will feel when I move back to civilization. Soon I’ll be walking on pavement and well-mowed grass again, rooming with strangers, and eating meals in a cafeteria crowded with more people than live within twenty miles of

this house. But I know I will come back. The back of beyond is home now.

1. chaparral: a dense thicket of shrubs and small trees

Click the two sentences that best support the inference that the narrator's expectations before the move were based on a kind of fantasy.

When my parents said the three of us were moving out to California, to a place just north of Los Angeles, my mind immediately went to thoughts of Disneyland and Hollywood, glitz and glamour. I imagined a Rodeo Drive shopping spree to pick out a bikini for the endless days I would be spending on the beach. However, I’d forgotten about my parents’ penchant for the unconventional; they’re definitely “the road less traveled” kind of people. Mom had a gopher snake for a pet when she was younger, and Dad was never happier than when she was younger, and Dad was never happier than when he was climbing near-vertical cliffs that only mountain goats could love. These are not city folk.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 218:

FILL BLANK

Read the text and answer the question.

Moving to the Back of Beyond

When my parents said the three of us were moving out to California, to a place just north of Los Angeles, my mind immediately went to thoughts of Disneyland and Hollywood, glitz and glamour. I imagined a Rodeo Drive shopping spree to

pick out a bikini for the endless days I would be spending on the beach. However, I’d forgotten about my parents’ penchant for the unconventional; they’re definitely “the road less traveled” kind of people. Mom had a gopher snake for a pet

when she was younger, and Dad was never happier than when he was climbing near-vertical cliffs that only mountain goats could love. These are not city folk.

They had chosen to buy a 900-square-foot cabin under a 250-year-old oak tree in the high chaparral1 forest out in the back of beyond – so far away from Los Angeles that you couldn't even see the glow of the lights at night. When I first saw

where we were going to live, I vacillated between feeling terrified and excited. This would be an adventure, for sure. But this was no camping trip where you could go home to civilization after a few days of roughing it; this was home, and

roughing it was the new normal.

On move-in day, we drove fifteen miles out from Antelope Valley – where the nearest grocery store was located – on a two-lane road past llamas, cattle, and horses. Up and up we went, until finally we turned down a dirt road and headed into

a canyon full of towering Coulter pines, blue-green sagebrush, and ancient canyon live oaks. I didn't know the names of these plants then, of course; I learned them later. That first day all I saw then was a million shades of green.

We parked under an oak tree that shaded our cabin and a front yard of rock, sand, and sagebrush twice as large as the cabin itself. On the stone staircase that led to the front door, black lizards interrupted their push-ups to twist their heads

and eye us as we passed. Scrub jays squawked and hummingbirds zoomed past the eaves, scolding us with their territorial calls.

No cars roared past. No radios blared from a neighbor's house. There were no neighbors – no human neighbors, anyway.

Our new home consisted of one bedroom, one bathroom, and one big room for everything else. A fireplace in the corner of the big room would be our sole source of heat in the winter. A swamp box (cooler) would blow a breeze over a big

damp pad to keep us cool all summer, or so my father said. But it was early autumn that day, and the temperature was perfect in the shade of the oak tree. Our oak tree, I thought; I was settling in.

Mom wiped a layer of grime off the kitchen counter and muttered about getting a bottle of bleach on our next trip into town. That was the beginning of an important lesson about living in the back of beyond: you don't just zip over to the local

convenience store anytime you need something out here. You have to make a careful list and check it twice so that you don't forget anything, because anywhere is a long way from here.

On my first walk around the property, I saw two horned toads, a red-tailed hawk, and some deer tracks. I wondered what else I might find deeper and higher in the canyon. Dad told me the real estate agent had mentioned that coyotes,

bobcats, mountain lions, rattlesnakes, and even bears roamed these hills. To my surprise, I found I couldn't wait to see them. All of them. I felt my feet taking root in the earth, claiming this place as home.

With no street lamps timed to turn on at sunset, when night came it was darker than anything I had ever experienced. Mom and I went out to look at the stars while Dad tried to unplug the ancient toilet. In the city, or even in the suburbs where

I had lived before, you could see only the brightest stars in the sky. But out here, it was like being in a planetarium, except there were no labels typed onto our sky. The sheer number and spread of stars was awe-inspiring.

That first night, we slept on air mattresses on the living room floor because the movers had not yet arrived. There were no curtains on the windows, so when the moon rose, it shone in as if moonbeams were an integral part of the cabin.

Eventually, I moved into the bedroom and Mom and Dad got a foldout bed for the living room. Over the next few months, I began to count the passage of time in full moons rather than by the pages of a calendar, and for the first time I really

noticed the days growing shorter in winter and longer in summer.

It's hard to believe, but we’ve been here for six years now. I’ve been going to school in the valley, but I feel most at home up here with my wild fellow canyon dwellers. Soon, I will have to leave home for college, and I’m a little afraid of the

culture shock I’m sure I will feel when I move back to civilization. Soon I’ll be walking on pavement and well-mowed grass again, rooming with strangers, and eating meals in a cafeteria crowded with more people than live within twenty miles of

this house. But I know I will come back. The back of beyond is home now.

1. chaparral: a dense thicket of shrubs and small trees

What is the author's message about living with nature? Use details from the text to support your answer.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 219:

FILL BLANK

Read the text and answer the question.

Blue Crabs Provide Evidence of Oil Tainting Gulf Food

Weeks ago, before engineers pumped in mud and cement to plug the gusher, scientists began finding specks of oil in crab larvae plucked from waters across the Gulf coast.

The government said last week that three-quarters of the spilled oil has been removed or naturally dissipated from the water. But the crab larvae discovery was an ominous sign that crude had already infiltrated the Gulf's vast food web – and

could affect it for years to come.

"It would suggest the oil has reached a position where it can start moving up the food chain instead of just hanging in the water," said Bob Thomas, a biologist at Loyola University in New Orleans.

"Something likely will eat those oiled larvae . . . and then that animal will be eaten by something bigger and so on."

Tiny creatures might take in such low amounts of oil that they could survive, Thomas said. But those at the top of the chain, such as dolphins and tuna, could get fatal "megadoses."

Marine biologists routinely gather shellfish for study. Since the spill began, many of the crab larvae collected have had the distinctive orange oil droplets, said Harriet Perry, a biologist with the University of Southern Mississippi's Gulf Coast

Research Laboratory.

"In my 42 years of studying crabs I've never seen this," Perry said.

She wouldn't estimate how much of the crab larvae are contaminated overall, but said about 40 percent of the area they are known to inhabit has been affected by oil from the spill.

While fish can metabolize dispersant and oil, crabs may accumulate the hydrocarbons, which could harm their ability to reproduce, Perry said in an earlier interview with Science magazine.

She told the magazine there are two encouraging signs for the wild larvae – they are alive when collected and may lose oil droplets when they molt.

Tulane University researchers are investigating whether the splotches also contain toxic chemical dispersants that were spread to break up the oil but have reached no conclusions, biologist Caz Taylor said.

If large numbers of blue crab larvae are tainted, their population is virtually certain to take a hit over the next year and perhaps longer, scientists say. The spawning season occurs between April and October, but the peak months are in July

and August.

How large the die-off would be is unclear, Perry said. An estimated 207 million gallons of oil have spewed into the Gulf since an April 20 drilling rig explosion triggered the spill, and thousands of gallons of dispersant chemicals have been

dumped.

Scientists will be focusing on crabs because they're a "keystone species" that play a crucial role in the food web as both predator and prey, Perry said.

Richard Condrey, a Louisiana State University oceanographer, said the crabs are "a living repository of information on the health of the environment."

Named for the light-blue tint of their claws, the crabs have thick shells and 10 legs, allowing them to swim and scuttle across bottomlands. As adults, they live in the Gulf's bays and estuaries amid marshes that offer protection and abundant

food, including snails, tiny shellfish, plants and even smaller crabs. In turn, they provide sustenance for a variety of wildlife, from redfish to raccoons and whooping cranes.

Adults could be harmed by direct contact with oil and from eating polluted food. But scientists are particularly worried about the vulnerable larvae.

That's because females don't lay their eggs in sheltered places, but in areas where estuaries meet the open sea. Condrey discovered several years ago that some even deposit offspring on shoals miles offshore in the Gulf.

The larvae grow as they drift with the currents back toward the estuaries for a month or longer. Many are eaten by predators and only a handful of the 3 million or so eggs from a single female live to adulthood.

But their survival could drop even lower if the larvae run into oil and dispersants.

"Crabs are very abundant. I don't think we're looking at extinction or anything close to it," said Taylor, one of the researchers who discovered the orange spots.

Still, crabs and other estuary-dependent species such as shrimp and red snapper could feel the effects of remnants of the spill for years, Perry said.

"There could be some mortality, but how much is impossible to say at this point," said Vince Guillory, biologist manager with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Perry, Taylor and Condrey will be among scientists monitoring crabs for negative effects such as population drop-offs and damage to reproductive capabilities and growth rates.

Crabs are big business in the region. In Louisiana alone, some 33 million pounds are harvested annually, generating nearly $300 million in economic activity, Guillory said.

Blue crabs are harvested year-round, but summer and early fall are peak months for harvesting, Guillory said.

Prices for live blue crab generally have gone up, partly because of the Louisiana catch scaling back due to fishing closures, said Steve Hedlund, editor of SeafoodSource.com, a website that covers the global seafood industry.

Fishers who can make a six-figure income off crabs in a good year now are now idled – and worried about the future.

"If they'd let us go out and fish today, we'd probably catch crabs," said Glen Despaux, 37, who sets his traps in Louisiana's Barataria Bay. "But what's going to happen next year, if this water is polluted and it's killing the eggs and the larvae? I

think it's going to be a long-term problem."

Excerpt from "Blue Crabs Provide Evidence of Oil Tainting Gulf Food Web" by John Flesher. Copyright © 2010 by The Associated Press. Reprinted by permission of The Associated Press.

Summarize the author's point about why scientists are monitoring the blue crab population so closely. Support your summary using key evidence from the text.

A.

See explanation below.

-

Question 220:

FILL BLANK

Read the text and answer the question.

Blue Crabs Provide Evidence of Oil Tainting Gulf Food

Weeks ago, before engineers pumped in mud and cement to plug the gusher, scientists began finding specks of oil in crab larvae plucked from waters across the Gulf coast.

The government said last week that three-quarters of the spilled oil has been removed or naturally dissipated from the water. But the crab larvae discovery was an ominous sign that crude had already infiltrated the Gulf's vast food web – and

could affect it for years to come.

"It would suggest the oil has reached a position where it can start moving up the food chain instead of just hanging in the water," said Bob Thomas, a biologist at Loyola University in New Orleans.

"Something likely will eat those oiled larvae . . . and then that animal will be eaten by something bigger and so on."

Tiny creatures might take in such low amounts of oil that they could survive, Thomas said. But those at the top of the chain, such as dolphins and tuna, could get fatal "megadoses."

Marine biologists routinely gather shellfish for study. Since the spill began, many of the crab larvae collected have had the distinctive orange oil droplets, said Harriet Perry, a biologist with the University of Southern Mississippi's Gulf Coast

Research Laboratory.

"In my 42 years of studying crabs I've never seen this," Perry said.

She wouldn't estimate how much of the crab larvae are contaminated overall, but said about 40 percent of the area they are known to inhabit has been affected by oil from the spill.

While fish can metabolize dispersant and oil, crabs may accumulate the hydrocarbons, which could harm their ability to reproduce, Perry said in an earlier interview with Science magazine.

She told the magazine there are two encouraging signs for the wild larvae – they are alive when collected and may lose oil droplets when they molt.

Tulane University researchers are investigating whether the splotches also contain toxic chemical dispersants that were spread to break up the oil but have reached no conclusions, biologist Caz Taylor said.

If large numbers of blue crab larvae are tainted, their population is virtually certain to take a hit over the next year and perhaps longer, scientists say. The spawning season occurs between April and October, but the peak months are in July

and August.

How large the die-off would be is unclear, Perry said. An estimated 207 million gallons of oil have spewed into the Gulf since an April 20 drilling rig explosion triggered the spill, and thousands of gallons of dispersant chemicals have been

dumped.

Scientists will be focusing on crabs because they're a "keystone species" that play a crucial role in the food web as both predator and prey, Perry said.

Richard Condrey, a Louisiana State University oceanographer, said the crabs are "a living repository of information on the health of the environment."

Named for the light-blue tint of their claws, the crabs have thick shells and 10 legs, allowing them to swim and scuttle across bottomlands. As adults, they live in the Gulf's bays and estuaries amid marshes that offer protection and abundant

food, including snails, tiny shellfish, plants and even smaller crabs. In turn, they provide sustenance for a variety of wildlife, from redfish to raccoons and whooping cranes.

Adults could be harmed by direct contact with oil and from eating polluted food. But scientists are particularly worried about the vulnerable larvae.

That's because females don't lay their eggs in sheltered places, but in areas where estuaries meet the open sea. Condrey discovered several years ago that some even deposit offspring on shoals miles offshore in the Gulf.

The larvae grow as they drift with the currents back toward the estuaries for a month or longer. Many are eaten by predators and only a handful of the 3 million or so eggs from a single female live to adulthood.

But their survival could drop even lower if the larvae run into oil and dispersants.

"Crabs are very abundant. I don't think we're looking at extinction or anything close to it," said Taylor, one of the researchers who discovered the orange spots.

Still, crabs and other estuary-dependent species such as shrimp and red snapper could feel the effects of remnants of the spill for years, Perry said.

"There could be some mortality, but how much is impossible to say at this point," said Vince Guillory, biologist manager with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Perry, Taylor and Condrey will be among scientists monitoring crabs for negative effects such as population drop-offs and damage to reproductive capabilities and growth rates.

Crabs are big business in the region. In Louisiana alone, some 33 million pounds are harvested annually, generating nearly $300 million in economic activity, Guillory said.

Blue crabs are harvested year-round, but summer and early fall are peak months for harvesting, Guillory said.

Prices for live blue crab generally have gone up, partly because of the Louisiana catch scaling back due to fishing closures, said Steve Hedlund, editor of SeafoodSource.com, a website that covers the global seafood industry.

Fishers who can make a six-figure income off crabs in a good year now are now idled – and worried about the future.

"If they'd let us go out and fish today, we'd probably catch crabs," said Glen Despaux, 37, who sets his traps in Louisiana's Barataria Bay. "But what's going to happen next year, if this water is polluted and it's killing the eggs and the larvae? I

think it's going to be a long-term problem."

Excerpt from "Blue Crabs Provide Evidence of Oil Tainting Gulf Food Web" by John Flesher. Copyright © 2010 by The Associated Press. Reprinted by permission of The Associated Press.

What inference can be made about the evidence the author uses to support claims in the text? Support your answer with evidence from the text.

A.

See explanation below.

Related Exams:

AACD

American Academy of Cosmetic DentistryACLS

Advanced Cardiac Life SupportASSET

ASSET Short Placement Tests Developed by ACTASSET-TEST

ASSET Short Placement Tests Developed by ACTBUSINESS-ENVIRONMENT-AND-CONCEPTS

Certified Public Accountant (Business Environment amd Concepts)CBEST-SECTION-1

California Basic Educational Skills Test - MathCBEST-SECTION-2

California Basic Educational Skills Test - ReadingCCE-CCC

Certified Cost Consultant / Cost Engineer (AACE International)CGFNS

Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing SchoolsCLEP-BUSINESS

CLEP Business: Financial Accounting, Business Law, Information Systems & Computer Applications, Management, Marketing

Tips on How to Prepare for the Exams

Nowadays, the certification exams become more and more important and required by more and more enterprises when applying for a job. But how to prepare for the exam effectively? How to prepare for the exam in a short time with less efforts? How to get a ideal result and how to find the most reliable resources? Here on Vcedump.com, you will find all the answers. Vcedump.com provide not only Test Prep exam questions, answers and explanations but also complete assistance on your exam preparation and certification application. If you are confused on your SBAC exam preparations and Test Prep certification application, do not hesitate to visit our Vcedump.com to find your solutions here.